The bird is dead. “To Kill a Mockingbird”1 has been taken off the school syllabus. Many of us must have wished that they had never seen, let alone write a paper on, the lauded book and had ardently prayed for the demise of the bird. However, even those who had borne through the boredom must be surprised to hear that the book has been banned, not for the lack of pictures or action, but for the “racial slur.” Talk about irony—its message was anything but. Yet owing to its incorrectly perceived politically incorrectness, that venerable but vulnerable paperback classic has been forced into retirement for precisely the reason that it was put on the syllabus in the first place.

Politically correct—what is? Race, gender, class and money—the more serious it is, the less we talk about it; and when we do, we talk around it. Soon it will not even be politically correct to talk about politics.

However, what is de facto not-politically-correct is the problems surrounding the mounting student loan: the situation is politically incorrect, financially grotesque and (potentially and probably) economically disastrous. How can it not be when the amount is a staggering 1.3 trillion USD? Seriously alarming, nevertheless, it is a topic that is given short shrift and shrugged off. Or maybe it is as serious as in “too serious to be taken seriously.”2

Student loan is growing. So what? More students go to college these days—19.9 million projected in fall 2018 vs. 15.3 million in fall 2000, with the highest enrollment so far in 2010 at 21.0 million3 (not very difficult to guess why). More the merrier, and more money.

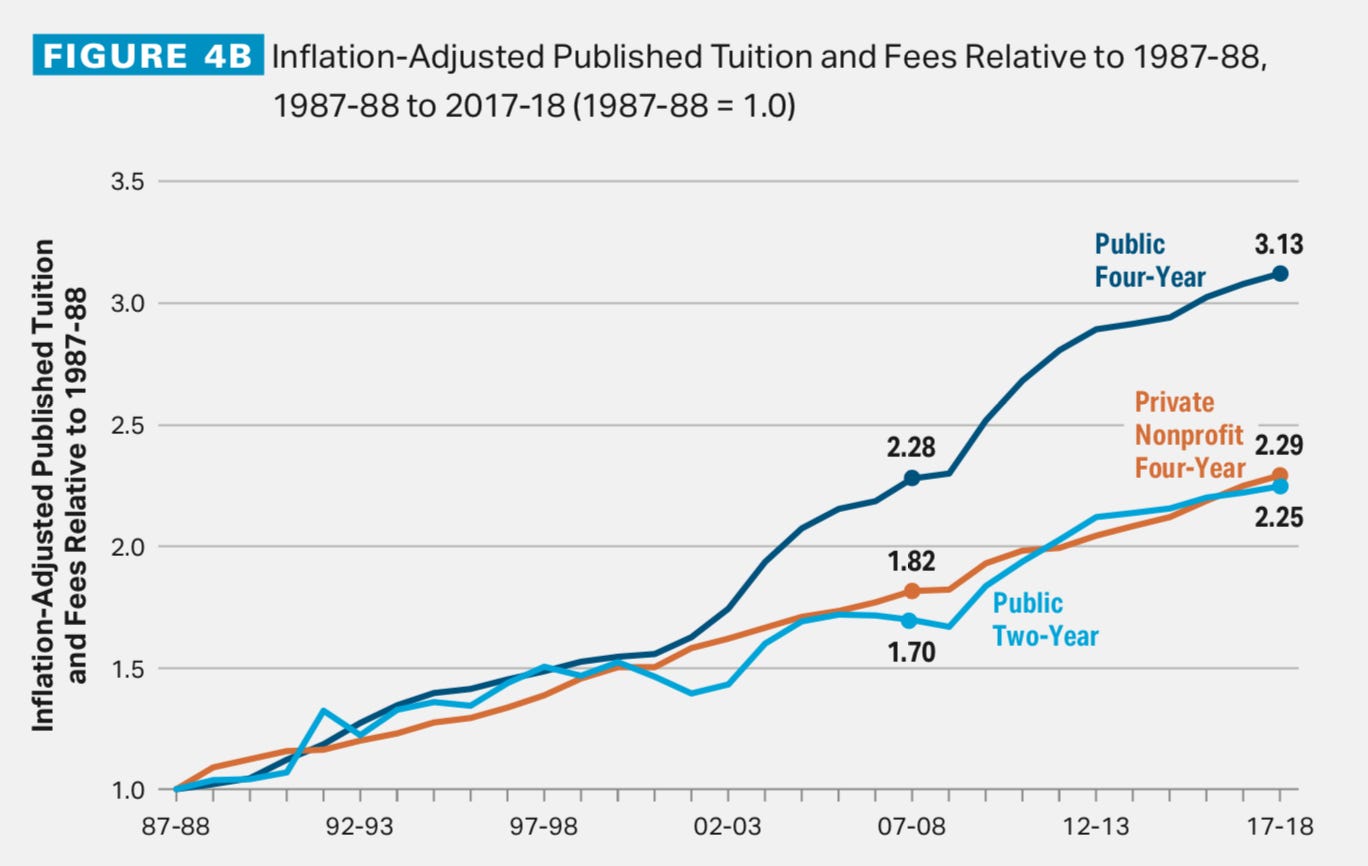

More students mean more borrowing. And more students also bring in more business for the school so that they need to invest in expanding their facilities and retaining their faculty. Profit or non-profit notwithstanding, whenever there is money, there is always margin for profit (or loss). As a result, not only there are more borrowers, but they are also borrowing more per head to cover the rising tuition.

All seems clear and simple: more college education needs more expenditure. It is the norm now to have a college education on the C.V., and ultimately, it is good for you anyway—to be educated. We want our young educated and stamped with BA’s and MBA’s and as much BS (no pun intended) as we can stomach, even if it is at the cost of delinquency and default. If ever in doubt, remember Sputnik and why student loan was created in the first place.

Loose underwriting, shaky credit, lack of collateral—give them a break. They are students; of course, they do not measure up on the credit score as grown-ups do. But education is one of the fundamental rights of human society—the building block of equal opportunity—hence it is not just a matter of profit. This is why the government must step in to provide direct loans to nurture these fledglings, and we all must unify in a dignified ambition “out of which all growth of nobleness proceeds.”4 Self-aggrandizement through education had thus been politically correct (especially around campaign times) and economically correct as education was believed to lead to higher productivity and profitability. “Increases in education levels since the 19th century have been estimated to account for between one-fifth and one-third of economic growth in the U.S.”5 and “on an individual level, the high returns to education reflect its impact on labor productivity, with an additional year of schooling providing an average 10 percent increase in wages.”6 Investment in human capital in the form of education, whether individually or collectively, had been the soundest and safest bet regardless of style—value or growth—or from whichever side—political, psychological or philanthropic.

We like growth—not in girth—but in economy, we like it very much. For the economy to grow, we need to develop the technology and human capital; and then, hopefully, there is a mastermind that can see beyond individual bickering and plan for the big picture.

Only the big picture was built on a big fairytale. Fairytale it was because, in this Land of Oz, also known as the United States of America, economic modeling seemed to have been premised on technology a little more advanced than the bran brain. But in the real world in the real time, technology has been galloping along, and like Frankenstein, in the spur of the moment, we have unwittingly created a monster called Artificial Intelligence. Humans have an idiosyncrasy to play God but, unfortunately, are not gods. Therefore, now that the creature is lunging to escape beyond human control to become truly intelligent—more so than its creator—and even sentient, we do not know what to do. Sure, it can work for us, this AI, so we can rest and play. However, in order to have the luxury of leisure, the current human monetary economy dictates that we need money first, which brings us back to the need of job and labor. But wait, our AI is going to take that away from us.

According to a report from the National Bureau of Economic Research7, one more robot per 1000 workers reduces aggregate employment to population ratio by about 0.34 percentage points (or by 5.6 workers) and wages by about 0.5 percent. But that is just one robot. What about one AI? What a conundrum. We have let the genie out and asked our wishes: higher productivity, higher GDP and more happiness for all. Alas, we did not make our wish exactly right—as we did not put in all the caveats and calculations as an AI would have.

Should we worry? The economy has recovered; the unemployment is low; and the United States is as healthy as it can hope to be, so much so that the Fed is raising the interest rate. The big corporations are earning big money; and the top earners are earning top dollars.

Take a close and cold look. Despite the low unemployment rate (3.9% in July 2018), the real average wage is not and has not been growing, and it “has about the same purchasing power it did 40 years ago. And what wage gains there have been have mostly flowed to the highest-paid tier of workers.”8 That is why education is important: they teach you about inflation in ECON101.

The relatively low level of education has been cited as one of the reasons for the lack of real increase in wages, which seems to provide all the more reason to seek higher education, if you want higher pay. Invest in yourself; you are the surest bet. Homeownership is no longer quite the American dream, is it? This current student loan default is just the growth pain that society has to bear. Like the teenager tantrum, borrowers will get used to the boost of hormone or money and grow up to be upright citizens, hand-in-hand with their new pet, AI, to safeguard human kind for ever and ever. 1.3 trillion USD in student loan is the necessary capital expenditure for this higher end and bigger pie.

Student loan is different from other types of loans. First of all, it is one of the biggest investments of a person’s life—and yet the interest is generally not tax deductible like other business investments or mortgage. Second, it is investment in human capital—an asset—but without a real collateral. Hence, it cannot be marked to market or subject to a stress test.

Student loan is an unsecured debt: lenders cannot seek recourse as in auto loans or mortgage by seizing the fresh graduates and put them on sale. Neither slavery nor human indenture is legal in all fifty states. Unsecured debut it is, yet it cannot be discharged in bankruptcy like credit card loans. In 2005, the bankruptcy laws were revised so that educational loans cannot be discharged unless the debtors can show “undue hardship”—an unduly hard hurdle. Furthermore, contrary to other unsecured debt, 93% of the outstanding student loan is held by the mother nation (or father, just to be politically correct).

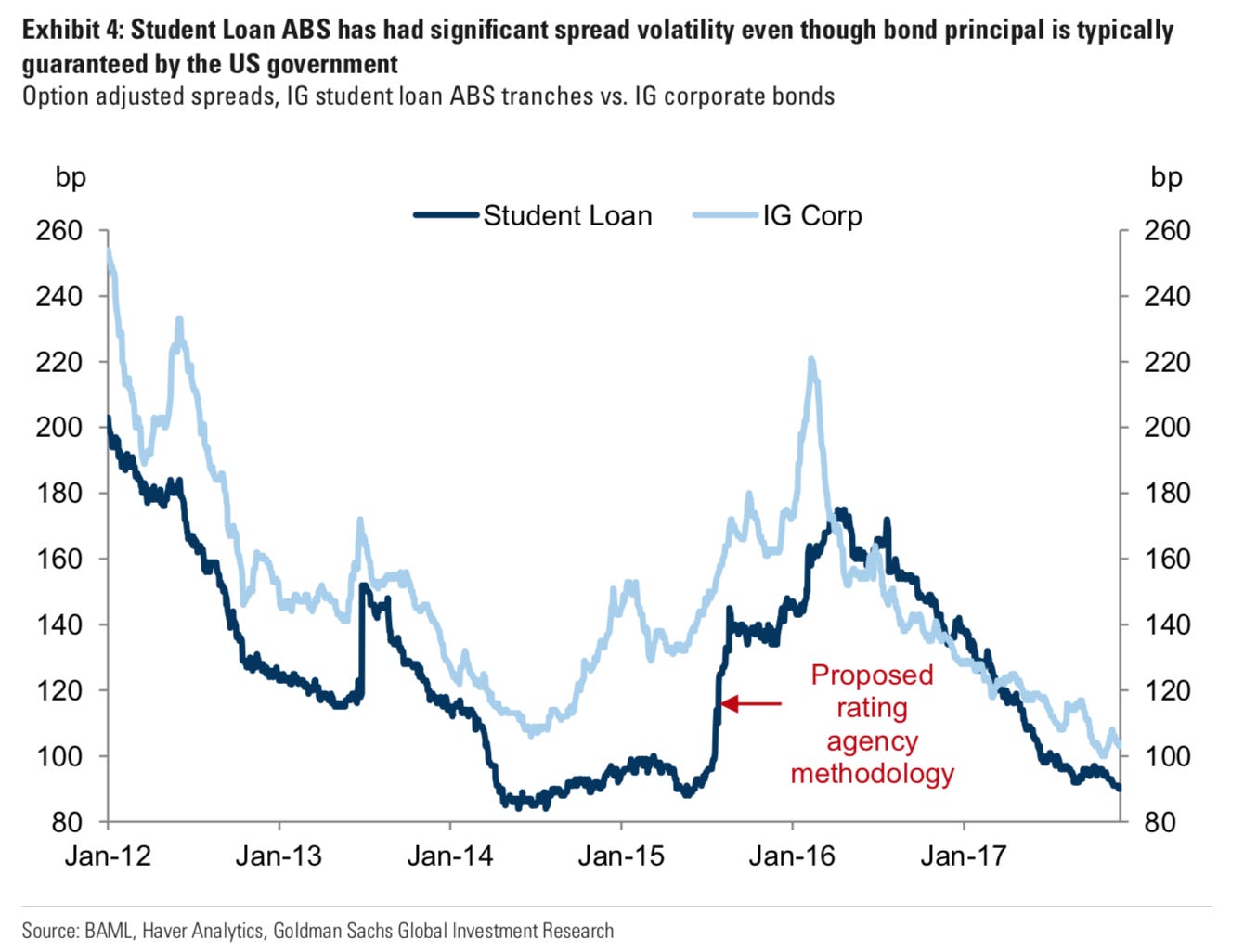

It is really not a big deal then as the burden of default ultimately falls on the Treasury, not us. 93% of the student debt is held by the federal government. “[T]he credit risk for the sector is mostly held on the US government balance sheet, we do not think student debt is likely to pose systemic financial risks.”9 “The biggest long-term risk is from public debt, with the Federal debt burden at close to 80% of GDP and headed for 100% in another decade’s time… But even a further rise in Federal debt to triple digit levels may not trigger a crisis, with other developed countries such as Japan and Italy coping…with even bigger debt burdens.”10 The debt is always greener on the other side—or not. Whatever the experts may say on the surface, the volatility of the securitized student loan seems to speak for itself.

For it is actually our money—our tax money. The subprime crisis and the subsequent bank bailout cost 700 billion USD in TARP; however, it is costing much more than that in reality. According to the estimate of Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, it will cost the average American 70,000 USD in lifetime income; or according to others, totaling 16 trillion USD or even 22 trillion USD—take your pick, they are after all estimates.

How much was the subprime mortgage again? Surprise, surprise—the estimated value happens to be 1.3 trillion USD in March 2007—the same amount as the student loan. But the student loan is still growing with no one pulling in the reins or putting on the brake.

In a recent interview,11 Ray Dalio said that the wealth gap today was the same as that in 1935-1940, and “with that wealth gap, you produced populism around the world.” In addition, the rivalry between China and the U.S. could disrupt capital flows and supply chain. Add student loan to that unsavory mix, are we set up for another financial melt-down? How many times can a nation bail out itself? Or, how many times can we save ourselves from ourselves? The economic repercussion is simply stupefying and seriously staggering when you realize that it is the future generation at risk this time—and it is our future, too. Super-sized house came with the problem of super-sized ego, but the ebullience and optimism still fueled us to grow psychologically in the good, old subprime era. Yet, now we are looking at a bleak future in the horizon, or just around the corner, as the effect is already creeping into the economy.

One in four graduates is burdened with student debt; and the average debt is $37,172.12 Thus already saddled, they do not exactly face a fresh start upon graduation. Various studies have already noted the decline in young homeownership, but the effect in other areas—i.e., cars, business ventures—vital for a healthy economy is still up in the air. No hope, no house and no money—that is the future without a future.

“There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County. But it was a time of vague optimism for some of the people: Maycomb County had recently been told that it had nothing to fear but fear itself.”13

To kill a mockingbird, Harper Lee, 1961.

No one else beats Oscar Wilde in witty quotes.

Paraphrasing, again, Oscar Wilde.

Barro, Robert and Jong-Wha Lee. 2015. Education Matters: Global Schooling Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Eileen McGivney and Rebecca Winthrop. 2016. Education’s Impact on Economic Growth and Productivity. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/educations-impact-on-productivity.pdf

By MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and Boston University’s Pascual Restrepo https://www.nber.org/papers/w23285.pdf.

Goldman Sachs. December 5, 2017. Global Markets Daily: US Student Loans: A Bubble, but an Unlikely Systemic Financial Risk.

Capital Economics, US Economics, October 11, 2018.

Here's how much the average student loan borrower owes when they graduate. CNBC. February 15, 2018.

See footnote 1, if you do not recognize it.