Yale Investment Office published the endowment’s 2019 performance (between July 2018 to June 2019). During the period, the endowment asset value rose 5.7%, bringing the total size to $30.3 bn. Some critics said the endowment model is not working as it underperformed S&P 500 significantly during the period and praised index fund investments. For example, Bill Abt, former CIO of Carthage College in Wisconsin, which manages about $123 mm, said Ivy League endowments “totally misplayed the market. They’re underperforming and their expenses are extra high with alternative investments.” Other critics argue that the US stocks are the best performer and will continue performing better than other markets. Although we focus on generating absolute returns, we need some “guidance” to measure our managers’ performance and often use S&P 500. Unfortunately, 99% of the managers, regardless they are long/short equity or long-only, underperform S&P 500.

Index Investment Makes Sense Only For Patient Investors

Actually, when I meet with a wealthy family with a relatively small asset base, I highly encourage them to follow the index investing. Instead of listening to private bankers’ smooth pitch and following their investment advice, which only enrich the bank and banker, not clients, it makes a total sense to create a portfolio using Vanguard funds and leave the portfolio for 3-5 years (with minor allocation adjustments). Unfortunately, many investors want to trade index funds and their trading habits add very little value, if not damage. Another problem is the index investing is quite boring and too stable. Many allocators want to add value by doing something and they often come up with a long solution like “Smart Beta”. The beauty of index investing is to remove your irrational judgment so that your portfolio is broadly diversified. Having said that, we also know that more than 1% of the managers we meet consistently generate superior return (although they may not outperform S&P 500) and we should stick with these managers. We have to pay high fees, but we can still generate better returns and we can also detach our emotional value destruction asset rotation from us. People generate returns after all.

Assets in Passive Funds Exceeded Active Funds For the First Time

Standard & Poor’s or Swine & Pork’s

Princeton’s Andrew Golden, protégé of David Swensen, admitted that the international markets were not a great to be. It is true that S&P 500 outperformed and retrospectively it was stupid to invest in non-US markets for sure (I’m talking about public markets in general, but it is probably the same for private markets, even including China).

Let me give you an example: due to the swine flu in China, the global hog price went up a lot over the last 12 months. In China, the wholesale price rose more than 100%, making Shanghai’s housewives worried about tomorrow’s dinner menu. If someone said, “pork was the best performer in the world over the last 12 months, so you should buy now,” would you follow his recommendation? I’m sure you won’t and the same goes to S&P 500. Golden said, “We don’t buy into the idea that U.S. stock market is the best benchmark or even the best context for what we do. That will prove to be wise when the stock market stops going from low valuations to extremely high valuations.”

As shown in the charts below, there are many evidences of relative expensiveness of US equity markets.

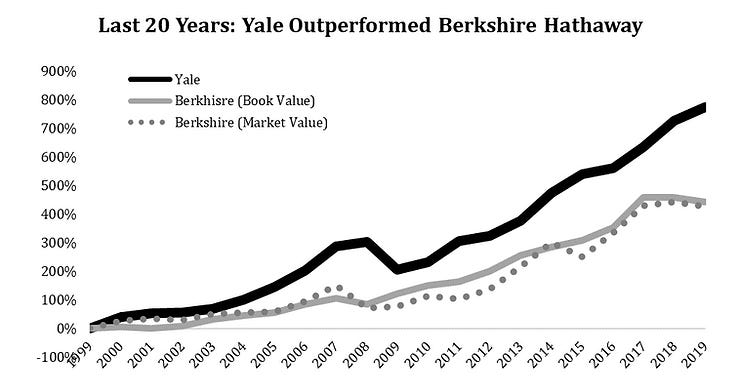

Yale vs. Berkshire

Over the last 20 years, which include two recessions, Yale managed to generate 11.4% annualized return. Even over the last three years, its 9.7% p.a. return outperformed Berkshire Hathaway with more than 3.0% p.a. although Yale’s performance was dragged by its international and absolute return exposures. I think Berkshire Hathaway is an interesting “benchmark” if you consider Warren Buffett as one of the best asset managers in the world’s history. If you invest in Berkshire Hathaway, you don’t have to pay the hefty performance fee since Buffett is not interested in drawing salary to maintain his modest life style (but, you are subject to pay tax, unfortunately).

More Ventures, More Buyout, Less Absolute Return

Yale only reports its target, instead of actual, allocation until its annual report is published later next year, however, we can analyze how Yale is thinking about its allocation decision. While it’s important to know the level of their allocation to each asset class, it is more meaningful to follow its trends. This year, we were able to identify three important trends.

Firstly, Yale started reducing its allocation to Absolute Return for the first time in the last 10 years. Unlike other endowments, Yale consistently increased target allocation to Absolute Return, making Absolute Return the largest asset class. This trend changed.

Secondly, Yale increased allocation to both Venture Capital and Leveraged Buyout (Yale does not have “Growth Equity” as an asset class). Yale’s asset allocation to Venture Capital consistently increased since 2005 without any up or down. The target allocation to Venture Capital is now 21.5%, tad below Absolute Return’s 23.0%. The increase was partially due to the appreciation of the underlying assets, but I believe Yale is adding capital to Venture Capital, instead of reducing.

Thirdly, Yale began increasing its allocation to Leveraged Buyout, reversing its earlier trend. The target allocation to Leverage Buyout peaked in 2015. Importantly, Leveraged Buyout is the asset class Yale added very little excess return over the last 10 years (although it was better than Real Estate). To me, it was a surprise as the investment environment in Leveraged Buyout is worsening as the availability of cheap debt keeps pushing the valuation multiple high.