Wealth, Caution

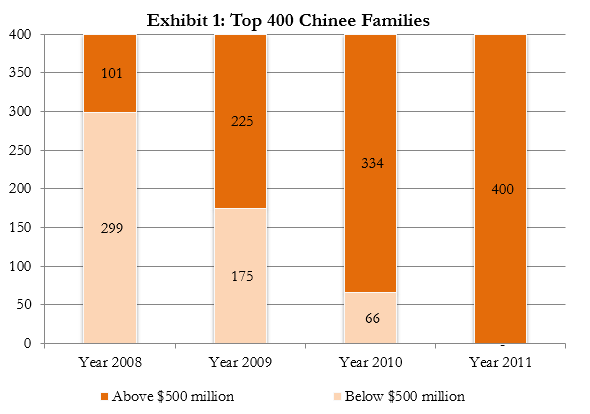

In 2011, Forbes estimated the top 400 Chinese families had amassed over $450 billion net worth (vs. $1.3 trillion of the 400 richest American families). Not the amount, but the speed of wealth accumulation catches our eyes. The wealth of the Chinese families grew 166% from the pre-crisis level in 2008, raising the minimum ticket size for this top 400 ranking to $500 million (See Exhibit 1). There are 111 billionaires in China by itself.

Despite the vast amount of recent wealth accumulation, Chinese families’ exposure to non-RMB assets is inconsequential due to the tight restriction on the currency exchange. Without the government’s permission, the amount of foreign currency Chinese citizens can obtain is limited to US$50,000 per year, no matter who you are. Over the last few years, a huge underground banking system was established and some private wealth managers offered this channel as a catch to attract clients (average haircut to “wire money” is said to be at 15-20%), but the risk of a behind-the-government transaction is too risky for most families.

As a result of the non-convertibility of RMB, many wealthy families have very high concentration on domestic assets, particularly in the property markets. The strategy worked quite well as they could return 40-50% annually over the last decade through massive infrastructure and residential development projects. I’m not bearish on China’s growth and property markets; however, the lack, or limitation, of asset diversification exposes Chinese families to a significant risk.

The Importance of Being Diversified

From 1960s to late 1980s, Japanese economy experienced an economic boom at a similar rate of China over the last decade. At peak in 1993, Japanese billionaires owned 13.4% of total wealth owned by all billionaires. Today, they only represent 1.6% of the total wealth and the decline was not surprisingly coincident with the real estate price (See Exhibit 2, next page). Shockingly, only 3 families (Busujima, Mori and Yamauchi families) out of the original 18 families on the 1990 and 1993 lists remained on the most recent list.

Investors in early 1990s hoped that the real estate slump was temporary. Most families on the 1990 and 1993 lists accumulated their wealth through the property boom and failed to diversify their assets away from the property and property-related businesses when the market was at the peak. Nobody could correctly predict how severe Japan’s economic slowdown would be, but they missed many opportunities to divest their assets and reinvest in overseas. The opportunity cost was apparently significant.

As a rule of thumb, you should never allocate a large portion of your capital in one country. Market risks are in fact relatively easy to diversify. Country and government risks are not. Japan is not a special case; any country can face a similar demise in a relatively short time period (if you disagree, please read Prof. Reinhart and Rogoff’s This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly). In order to protect wealth and legacy over multi-generations, European and American families learned how to diversify their wealth, but it took them a lot of time. Better to take an action earlier than it becomes too late.

A good investor always learns from a mistake. And, it is even better if you can learn from someone else’s mistake. Although it’s difficult for most Chinese families to access foreign currency assets, they can and should start preparing because it takes a really long time to achieve global diversification, financially and mentally.